Lost Soul Sister: Dee Dee Warwick

There are plenty of lost sisters in the shadowy realm known as ‘session work.’ Session musicians, after all, are the bedrock upon which the constructs of ‘talent’ are built – those singular edifices that come to signify entire musical landscapes.

Dee Dee Warwick is not as lost as some; her voice can be found outside of the bread-and-butter work she did as a session backing vocalist. Since she circulated during one of the most prolific and productive periods of the New York-based music industry, she has a healthy discography of solo single releases, five solo LP’s, and two recent compilation releases – one representing her Mercury days and the other, her Atco Days.

Despite these distinct advantages, Dee Dee is indeed a lost sister. On a production level, much of her solo recording is done in a way that does benefit her most soulful contralto voice. Beyond the music, it is hard to get a hold of a good write up of her accomplishments. There are slim readings to be found, mostly obituaries, and a few promo articles from back in the day buried on Rock’s Back Pages. In what can be found, it is impossible, it seems, for writers and publicists not to inculcate into their coverage of her career the names of her more famous Warwickian kin or the R&B megastars of her era.

And yet, there is reason not to let her languish in the shadows of the R&B / Soul canon. Even though much of the time you need to listen past the production strategies that failed her and wade through the constant referencing of a constellation of talent from which she emerged – and, in the end, into which she submerged (her last gig was doing backings for her sister Dionne) – it is worth getting to know Dee Dee’s work. Hers is a voice of DEEP soul – talent that can’t be found looking through popular lenses or accessed via the usual channels that deliver us the stories of industry powerhouses. You got to dig for it by listening.

Hers is a career that exemplifies what happens when the current standards don’t have a niche for a particular mode of talent.

And because of this fact, Dee Dee Warwick’s legacy is not without its ironies and illustrate the entrapments the music industry lays for some artists. But with an avid ear, you will hear a voice soulful and expressive of what the blues is all about, of a depth that indicates a personal lode of experience in singing through whatever the harsh times bring you.

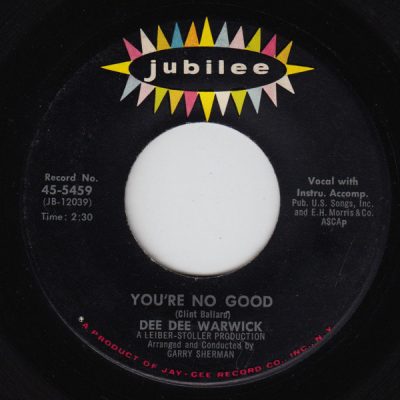

At the outset, one finds what, arguably, is her best-known recording: ‘You’re No Good’, a song written by Clint Ballard and first cut with Dee Dee’s vocals and Garry Sherman’s arrangements on a Leiber and Stoller production for Jubilee Records in September 1963. Dee Dee’s is a performance of heft and grit, vulnerability and resolve, and brings with it all the singing traditions in which she was raised and trained. The recording starts – and stays – at a low register, a sweet spot for Dee Dee’s contralto. The instrumentation is simultaneously beat out with a distorted snare drum and cowbell punctuation while finessed with syncopated rhythms, yet it does not get in the way, as accompaniment often does for ‘girl groups’ (gratefully there is a distinct lack of strings, that devouring, over-emoting bedding device of choice for arrangers of the era). The bass stays a constant, solid thump creating space for the infrequent interludes of horns, honky-tonk piano, and a momentary fuzztone, single-noted guitar solo.

All of which allows Dee Dee’s vocals rise up and drive the song from the start with a blues shouter’s command and theatricality that conveys the raw, emotive double edge of the various ‘Yous’ in the song. Her call-and-response with the backing vocals (“hey-oh-hey-oh-hey-hey”, “ah-ha-hah”) evokes a gospel fervor and does justice to the complicated position of the imagined singer. Is she testifying to the one that’s no good? To her girlfriends? To herself? The inflections of Dee Dee’s singing traverse a multitude of emotive states – pride, bittersweet realization, hopeful torment, determination – all in very compact verses (listen to the ‘no good / no good / no good / not / for me / any MORE’ at the end of the song). What you hear from Dee Dee’s performance is what James Baldwin described as a “freedom that one hears in some gospel songs, for example, and in jazz. In all jazz, and especially in the blues, there is something tart and ironic, authoritative and double-edged.”

And yet, and yet. ‘You’re No Good’ did not chart for Dee Dee. The September 1963 edition of Billboard lists the song in its Pop Spotlight Singles Review using the terms ‘earthy’ and ‘hard-hitting’ – veiled indicators that the industry cookie cutter made from gendered and racial biases wasn’t going to fit. As such, her performance fell prey to the effects of that great grinding and mining enterprise that is the music industry – what can be called Version Obscura.

‘You’re No Good’ has been recorded ad nauseam and most likely, readers are more familiar with one of these later, lesser versions. There is the demur, Bossa-bluesy version cut by Betty Everett (another lost sister) for Vee-Jay Records just two month’s after Dee Dee’s. This tame version, with the back-ups axed and the register safely in the soprano zone charted and immediately erased what came before. There is also the mega-hit that Linda Ronstadt took to Billboard’s coveted Number 1 spot in 1975. And though Ronstadt’s vocals are expressive, the song is not best fitted to her ranchera style and burdened by a confused guitar solo that tries to be both reminiscent of both 1960s fuzz-tone and later Beatles. Ronstadt herself has even been quoted as saying, “As a song it was just an afterthought. It’s not the kind of song I got a lot of satisfaction out of singing.”

And there are others: the 1964 gender inversion recording sung by the bubblegum boys of the British outfit, The Swinging Blue Jeans; the 1967 campy and sultry personality vehicle for Julie London that has her pillow-talking vocals over a swollen backing arrangement; the abomination that is Van Halen’s unspeakably sour 1980’s handling of the composition; even Reba McEntire got in on the action in 1995 without bringing much new to the cut. Point being, what could have marked the start of a unique talent’s solo career is really now a palimpsest, written and re-written, the perennial cover, obscuring and effacing Dee Dee’s original rendering (one caveat: Frankie Rose and Outs did a great version that pays homage to Dee Dee’s performance in their recording for the Aquarium Drunkard blog).

The song’s various reincarnations would not be Dee Dee’s last encounter with version obscura. Beyond ‘You’re No Good’, Dee Dee did a recording of ‘Alfie’ in 1966, only to have her sister Dionne re-record and chart it in 1967. She also cut ‘I’m Gonna Make You Love Me’ in 1967 (with Ashford and Simpson on backing vocals) to have it overshadowed by the power-crossover hit done by The Supremes with the Temptations in 1968. These songs differ from ‘You’re No Good’ however, in that they suffer from another pitfall that would plague Dee Dee’s career: they force her into an upper register without giving her the leeway to get there in her own sweet time. It’s not that Dee Dee can’t perform in the upper register; it’s just that she needs a range that grounds her in a lower compass point to get her there.

Take ‘Gotta Get A Hold of Yourself’ and ‘Who Will Be The Next Fool Be’ as two examples, the former from her early Mercury days and the latter from the Atco era. Both have her traveling to the upper registers, but they don’t force her to stay there and abdicate the soul she’s capable of the alto zone. In ‘Gotta Get A Hold of Yourself’, Dee Dee moves and flies around the higher belt-out notes but gets to alight often to the lower range. And though ‘Who Will The Next Fool Be’ is predominately in a higher register, the valence of the lyrics is sweeter, rather than that which requires sustaining power ballad high tones. So whereas ‘You’re No Good’ showcased what Dee Dee was all about, compositions like ‘Alfie’ and ‘I’m Gonna Make You Love Me’, subsequently and all too quickly re-recorded, failed her from the beginning.

Even Dee Dee herself had releases using the version obscura strategy. Her much lauded R&B treatment of ‘Suspicious Minds‘ is a powerhouse performance. The interlude at the end of the song has her moving effortlessly between quiet, heartfelt intonations infused with forceful longing. But one wonders what her producers were thinking having her compete with, you know, ‘The King’: Elvis Presley’s version of the song was still on the charts when she released her version in 1970.

Other production deficits add to the mix and fail to bring the spotlight to Dee Dee’s talent during the sporadic efforts she made at a solo career in between her rock-solid session work. And ironically, one of the worst production failure is what can be called ‘Session Inversion’ – when the back arrangements or backing vocals upstage the main vocals in volume or type, as if producers think the backing has to overcompensate around such a powerful voice. Examples fall on spectrum ranging from egregious (the incredibly misplaced yodely backing vocals on ‘If This Was The Last Song’) to distracting and cloying (the harp in ‘Another Lonely Saturday’) to oversaturated (the mix of echoed-out main vocals and too forceful backings on Dee Dee’s charting ‘Foolish Fool’).

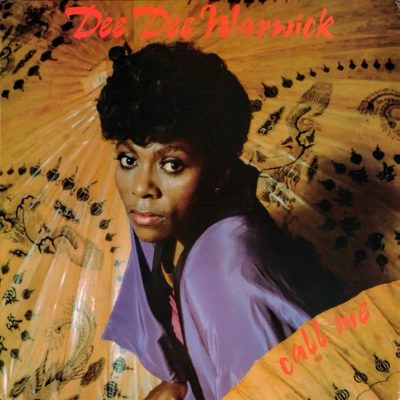

Sometimes such a production angle is understandable, particularly in the case of the recordings Dee Dee did with the Dixie Flyers, as one assumes the producers wanted to showcase their talents as well. And other times, session inversion can be forgiven, as with Dee Dee’s Sutra Records album, ‘Call Me’ where all the pervasive, manufactured tricks of the disco era can be heard. And thankfully, on the rare occasion, session inversion is avoided as on the stunning presentations found in ‘A Cold Night in Georgia’ (listen to Dee Dee roll with those key changes) and on the soul-to-the-bone ‘Down So Low’ that lets Dee Dee gospel-steeped voice keep the focus. Sure, not all vocalist get accompaniment capable of the nimble precision and vision of say, Teddy Wilson, but the above treatments will never be found on productions for, say, Barbra Streisand. The full effect of these predicaments, combined and accrued, is one that keeps from view Dee Dee’s talent, and reveals the industry machinations often employed to twist originality into common molds.

And yet, and yet: despite these shortcomings, Dee Dee’s voice is there, full of soulful artistry and potential that one wishes could have found a footing. It’s not surprising, then, that the recent digital release of the Atco complication, doesn’t feature Dee’s face, with its high-cheekboned intensity and asymmetrical beauty, but a flattened, silhouetted placeholder. To be fair, all of the Atco digital compilations have this art direction, not just Dee Dee’s. One wonders if the designers were aware of the fresh erasure such an unfortunate graphic perpetrates. Perhaps that is what they are trying to call attention to? Regardless of whether your reading of the artwork is sympathetic or damning, in Dee Dee’s case, the visual is apt.

And that is because Dee Dee Warwick is not an artist you can see. You won’t see her floating around in the glittery light of a Burt Bacharach tune (like Dionne). You won’t see her getting rowdy all over a scale (as only Aretha can) in a major motion picture. There are no audio-visual depictions of her story to watch, whether in the form of redemptive narrative (like Tina’s) or tragedy (like Whitney’s).

No, Dee Dee Warwick is an artist you have to hear. And even that’s not easy.

But the reward for the work of giving an ear for listening is the sound of a voice that is as deep as the roots that can sometimes grow in the bedrock and remain – lucky for us – no matter what gets built up or torn down overhead.

Source: Perfect Sound Forever: Dee Dee Warwick, by Cat Celebrezze (April 2017)